Christmas is a happy time, right? Okay, I know there are people who immediately groaned when they read that. Some of my friends turn into Ebeneezer Scrooges immediately after Thanksgiving (though I won’t name any names). In general, though, Christmas is a time of joy and celebration, a time for televising the umpty-umpth rerun of every Rankin-Bass Christmas cartoon ever animated, for getting drunk on spiked eggnog and mulled wine, and for listening to Christmas music on the radio, your iPod or your favorite streaming music service. And Christmas music must be the happiest music ever written. Right?

Not necessarily. It took Amy, who being Jewish has a somewhat different perspective on Christmas music than I do, to point out what should have been obvious to me years ago: A lot of modern Christmas songs, maybe more Christmas songs than not, are real downers.

I’m not talking about religious Christmas music, which is mostly about how thrilled the singers are over the birth of their savior. And I’m not counting Greg Lake’s “I Believe in Father Christmas,” which isn’t really a Christmas song so much as it’s a “bitter-rejection-of-Christmas” song.

When you get into secular Christmas music, though, the landscape starts to change. Sure, songs like “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” and “Let It Snow” are so upbeat that they make you want to dance. “The Christmas Waltz” even tells you what dance you’re supposed to dance to it. But a surprising number of pop Christmas songs are about how depressing a time of year this can be, especially if you want to be someplace that you’re not or with somebody you can’t be with.

I don’t know if it was the first depressing Christmas song, but Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas,” at one time the most popular Christmas song in the Great American Songbook, is definitely a sad song. As the rarely used intro says, “It’s December the 24th and I’m longing to be up north.” It’s about a person (probably Irving Berlin himself, stuck in Los Angeles writing songs like “White Christmas” for the movies) having a somber Christmas because it’s not “like the ones [he] used to know.”

During World War II, there were thousands of GIs who wouldn’t be home for Christmas because they had a war to fight in Europe and Japan. The 1943 song “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” acknowledged this by painting a picture of a perfect Christmas homecoming — “We’ll have snow and mistletoe and presents under the tree” — then blowing it apart with what may be the most heartbreaking punchline of any song from that era: “I’ll be home for Christmas…if only in my dreams.”

By the 1960s, Elvis Presley was singing about having a “Blue Christmas” (a song actually written in the late 1940s), lamenting that the object of his affections would “be doing all right with [her] Christmas of white, but I’ll have a blue, blue, blue Christmas.” (Three “blues” in a row. Can’t get much bluer than that.) The song was a huge hit and still gets played, in versions by Elvis and dozens of others, every Christmas. And note how it neatly references the Irving Berlin song, not only in its title but in that line about “in your Christmas of white.”

It may have been Karen Carpenter, though, who really started the sad Christmas ball rolling with 1970’s “Merry Christmas, Darling,” a song written by her brother Richard in collaboration with Frank Pooler and not made any happier by the fact that Karen died a much-too-early death a little more than a decade later. It’s a sweet but heartbreaking song about a woman separated from her beloved for unspecified reasons and remains one of the greatest Christmas songs to come out of the 1970s.

The Karen and Richard Carpenter Center for the Performing Arts, made relevant only by the fact that we saw David Benoit and his trio perform a tribute to A Charlie Brown Christmas there a few nights ago

Dan Fogelberg must have been drinking from the same pain-spiked bowl of eggnog when he wrote and sang 1980’s admittedly rather sappy “Same Old Lang Syne,” a song that’s often played as a New Year’s song, but that takes place on Christmas Eve. In it, the singer meets an old girlfriend who apparently broke his heart long ago and who is now in a loveless marriage with an architect. (Honestly, Dan, I don’t know how you got through the song without gloating — unless the whole song is one big gloat.)

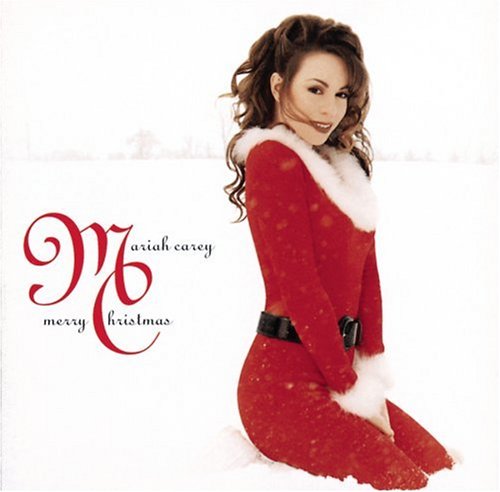

It’s hard to say if Mariah Carey’s 1995 Christmas hit “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” released again in 2011 as a duet with Justin Bieber, is a happy song or a sad song, given that she leaves us hanging in the end as to whether the person she loves leaves her standing, kissless, under the mistletoe. The uptempo arrangement suggests that this is really a happy Christmas song, but we don’t know for sure. Come on, Mariah. End the suspense and tell us if Mr. Right finally showed up! (Given that formfitting Santa suit you’re wearing on the album cover, I’m guessing he did.) And feel free to give me one of those presents under the tree that you seem so uninterested in. I’m guessing there’s some pretty expensive stuff in there.

Yeah, I’m sure the guy never showed up, maybe because her then-husband Tommy Mottola would have had his fingers broken.

When talking about sad Christmas songs, though, there’s one that leaves all the others in the dust (or snow) and you certainly wouldn’t guess it from the song’s name: “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” As sung by Judy Garland in the 1944 film Meet Me in St. Louis, it’s about a family being torn apart from friends and relatives, not to mention having to miss the 1904 World’s Fair, because of their father’s job in New York. Garland sings the song to comfort her little sister, played by Margaret O’Brien, but that didn’t prevent lyricist Hugh Martin (who had written the song many years earlier) from having to change lyrics like “Have yourself a merry little Christmas./It may be your last./Next year we may all be living in the past” to their marginally more cheerful versions in the film. And when Frank Sinatra recorded the song, he asked Martin to “jolly up” the lyric “Until then we’ll have to muddle through somehow.” It became “Hang a shining star upon the highest bough.” Ironically, when Judy Garland sang the song to her daughters on television in the 1960s, she sang the Sinatra version rather than the one she had sung in the film.

The truth is, Christmas music is like all other types of pop music. There are sad songs, like the ones we’ve discussed. There are upbeat songs, like “Sleigh Ride.” And there are dance songs, like “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree.” Christmas may be a happy occasion — although we’ve been told many times that suicides soar around the holidays, Snopes.com says that’s just an urban legend — but the truth is that we’d eventually get sick of hearing nothing but cheerful music.

I say bring on the heartbreak songs, if only because sometimes it brightens your day to learn that someone else’s life is going even worse than yours is.

UPDATE: After I posted the column above, Amy and I discussed some other downbeat Christmas songs. The most obvious was Wham’s 1984 “Last Christmas,” which earns its sadness rather cheaply: The singer apparently had a one-night stand last Christmas and expected it to outlast the holiday. It didn’t. Another Christmas song that could conceivably be seen as a downer is “My Grown-Up Christmas List,” a much-covered Amy Grant hit from 1990. Although the song is hopeful — it’s about an adult who asks Santa Claus to cure everything that’s wrong with the world — it requires the singer to list all of those things and that’s the downer part. “What,” the singer asks, “is this illusion called the innocence of youth? Maybe only in our blind belief can we ever find the truth.” Upper or downer? Your call.

My vote for most suicide-inducing Christmas song of all time, though, goes to “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” which has lyrics taken from an 1863 poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called “Christmas Bells.” Depressed by the death of his wife and the even more recent death of his son in the American Civil War, the poet wrote:

And in despair I bowed my head

“There is no peace on earth,” I said

“For hate is strong and mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep

The Wrong shall fail, the Right prevail

With peace on earth, good will to men.”

I suppose Longfellow was trying to find hope and meaning in the tragedies he had been through, but there’s a sense that he doesn’t believe a word of it. If “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is about a family falling apart, “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” is about a world falling apart. It makes “Merry Christmas, Darling,” where the missing lover is at least alive and presumably coming back some day soon, sound positively cheerful.