So where were we? In the first two parts of this series on video games as virtual reality, I talked about how in 1981 I’d had a vision — not a full-blown clairvoyant vision with my eyeballs rolling backward in my head but more of a daydream about the future — of a time when computer game programmers would create games so realistic that playing them would be like entering an actual world and interacting with the objects and the people there. I talked about how various games, like the SubLOGIC/Microsoft Flight Simulator and Doom had upped the ante on realism in computer graphics to the point where, today, we have games in which the world you see on the computer screen is almost indistinguishable from an actual video. It’s as though game designers can invent an entire planet, populate it with intelligent beings, wait a few million years for those beings to build infrastructure and then let the player carry a camera to that planet and snap pictures of it. Take a look at this screen shot from developer Crystal Dynamics’ recent reboot of the Tomb Raider series:

The new, photorealistic Lara Croft

If you’ve played the game (and I strongly recommend it, even if you hated the old Tomb Raider series where Lara Croft looked like a Barbie Doll on steroids) you know that the jungle village the young Lara is entering isn’t a painting or a photo but a detailed three-dimensional model that you, the player, can explore in almost breathtaking detail. The pulleys and elevators actually work (in a virtual kind of way), the wooden surfaces are detailed down to the smallest splinter, and those mountains in the background really can be climbed, at least where they aren’t too steep. And this village is only a tiny fraction of an entire tropical island filled with lovingly designed and vividly rendered sets. (Unfortunately, while this new version of Tomb Raider is better and more playable in almost every way than the old games were, it suffers from one flaw of the original: Lara still tends to fall down and die a lot. But the game itself is so good that I found I really didn’t mind that much.)

Essentially, the graphics problem facing designers of realistic virtual reality games has been cracked. The worlds in modern games can look real, at least if the game designers want them to. (Some game designers deliberately opt for nonrealistic graphics, the way painters in the 19th century began opting for impressionistic images on their canvasses rather than photorealistic ones.) But to my mind the best games are based around stories and story is a more difficult problem than photorealistic graphics, because it can’t be cracked using mathematical algorithms executed by extremely fast multiprocessing CPUs, at least not any algorithms that are on the game-design horizon at the moment. Putting a story in a game isn’t like putting a story in a novel or a movie, which writers and directors have been doing since long before any of us were born. A game story has to be interactive, capable of changing according to decisions made by the player, and that creates a paradox. A story is a series of events with a dramatic shape, building to a climax, but a story shaped by a player could easily collapse into a mass of unrelated events that are about as interesting as watching a traffic jam on the Los Angeles freeways. How can game designers reconcile story and interactivity without creating chaos?

In my 1981 vision, I imagined that artificial intelligence would have been developed sufficiently by now that the game designer would merely have to create a world that had the potential for story and each player would find their own story in that world. For instance, the game could be set in a Central American country on the verge of revolution with a well-meaning but hot-tempered dictator whose beautiful wife is thinking about having an affair. You, the player, would be an American reporter who could choose to get to know the dictator, the leader of the revolutionaries and/or the dictator’s wife and interact with them in ways that could shift this explosive situation in an almost infinite number of different directions. If these characters were full-blown artificial intelligences, the results of the story would be genuinely unpredictable. Even the game designer would have no way of knowing how events would proceed or what the ultimate results would be for each individual player. That’s a game I’d love to play. Game developers could create that game today — maybe they already have — but it would be a cheat. The game designer would have to create certain story paths in advance that would be affected by decisions you make, each decision making you more likely to go down one path than another. And, in fact, plenty of such games have been created and it’s these predetermined story paths that create what happens in the course of game play. Still, the game designer has a certain amount of leeway in how much freedom they actually give the player and how many different predetermined paths the game can take. At one extreme, this type of game design can produce an open world with so many possibilities for story that it comes very close to being the kind of game I envisioned back in 1981. At the opposite extreme, the number of game paths is so limited that the player only has the illusion of free choice and is channeled down a single predetermined story path with only minor variations along the way. Let’s call the first kind of game an Open World game and the second kind of game a Closed Story game. A really clever game designer can create a game that combines both approaches and, in fact, many designers have. We’ll call this the Open Story game. In the rest of this post, I’m going to describe (and review) three games from the last two or three years, each of which takes one of these approaches. For the Open World game, I’m going to talk about The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim from Bethesda Design Studios. For the Closed Story game, my example will be The Walking Dead: Season One from Telltale Games. And for the Open Story game, I’ll describe Dishonored from Arkane Studios. Let’s start with the first:

The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim

Back in the first installment of this post, I talked about how I’d seen the first Elder Scrolls game, Arena, in development in 1993 at Bethesda Softworks back when I lived around the corner from their offices and had my mind genuinely, if not literally, blown by what I saw. My mind was even further blown — honestly, I don’t have much of it left — when I saw the game itself. It created an entire continent, Tamriel, and let the player travel across it to complete a lengthy quest. Along the way you could pursue hundreds, perhaps thousands, of side quests and visit hundreds of cities and dungeons, some of which would appear on the game map from the beginning, allowing you to fast travel to them (saving a lot of walking time), and some of them you just had to discover by talking to people or wandering around the countryside, at which point they would appear on your game map. I had always loved the exploration element of computer role-playing games, ever since I played Ultima III on my Commodore 64 back in the mid 1980s, and Arena had the hugest world I’d ever explored. The graphics were low-resolution by modern standards and most of the dungeons were algorithmically generated, so that after a while they started to look alike, but I was stunned by the sheer size of Arena’s world. I still am when I go back and play it using the DOSBox-emulation program. With each subsequent Elder Scrolls game the world has grown smaller — most of the later games have restricted themselves to a single province of Tamriel — but it’s also become more detailed. Skyrim restricts the action largely to the eponymous province, but dear God is it detailed! And it feels huge, as big as the whole continent of Tamriel did in Arena. It contains a multitude of environments, from forests to mountains to arctic wastes, and you can’t go far without stumbling on ancient ruins, tiny villages or someone just spoiling to lock weapons with your character. There’s no plot forced on you in Skyrim, but the opening sequence, where you nearly get your head sliced off on a chopping block, hints that there are larger conflicts involved and it isn’t long before you find out what they are. You can choose to engage in these conflicts or not, and if you choose to do so you can either pick sides or never get around to picking sides. Mostly Skyrim provides you with a world to live in and explore. (You can buy your own house in several of the game’s many cities and the game DLC — downloadable content — even supplies a feature that lets you build your own log cabin from materials you forage in the wilderness.)

Skyrim: Not so much a game as a world to live in

Skyrim comes about as close as any game I know to that game I envisioned more than three decades ago. It still doesn’t feature true artificial intelligence — the game’s many quests and character interactions are still pre-scripted — but the number of ways in which you can combine the game’s dozens of quests and personal choices, along with the sheer exploration element and the games smooth, unforced system of gradual character building make it feel like an RPG version of the old SubLOGIC Flight Simulator. You really do feel that your game experience in the Skyrim world is unique and that while thousands if not millions of players have probably fought the same battles that you have, the way in which you combine the events that make up your character’s life, the total experience that you have in the game, may be different from anyone else’s. There’s a story in Skyrim — actually, there are multiple stories — but after hundreds of hours of play I’ve yet to figure out what the end of it is or even if it has an end. Out of the many characters I’ve created, the one that I’ve worked up to level 45 on my Xbox has come up against a dragon encounter that has an awfully climactic feel to it, but he wasn’t capable enough to handle it, so I reset to the last saved game and sent him off to deal with some of the game’s other plot elements, like the battle for secession being fought between the Skyrim rebels and the occupying army sent by the Empire to put them down. My various characters have chosen to fight with the rebels and with the Empire. Both factions have strong arguments in their favor and notable moral flaws. Sometimes I choose not to get involved with them at all and just busy myself with a little dungeon diving, returning magical artifacts to the NPCs — non-player characters — who’ve asked me to retrieve them. Last night I looked at the number of quests I’ve completed in the Xbox version and was startled at how long the list has become and yet there are whole towns full of people I’m afraid to talk to lest they add dozens of new quests to the list of ones I’ve yet to complete. The very fact that Skyrim has this degree of complexity and no obvious goal for the player to work toward other than the goal the player selects for him or herself is one of the many things that make it feel real. It has a story, but in many ways the story is what you make it. The game designers never force you to do anything, except defend your life when attacked by a hungry wolf or marauding bandits. Rather, the story of the game is what you choose to make out of what may well be hundreds if not thousands of possible quests and decisions, and if you’re not interested in story you can simply explore the world and look at the scenery, playing it as a sandbox game. In Skyrim, you come about as close to shaping your own experience as in any game I’ve ever seen.

The Walking Dead: Season One

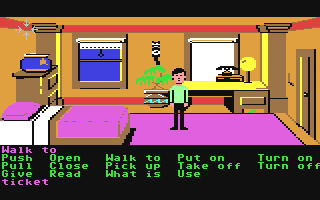

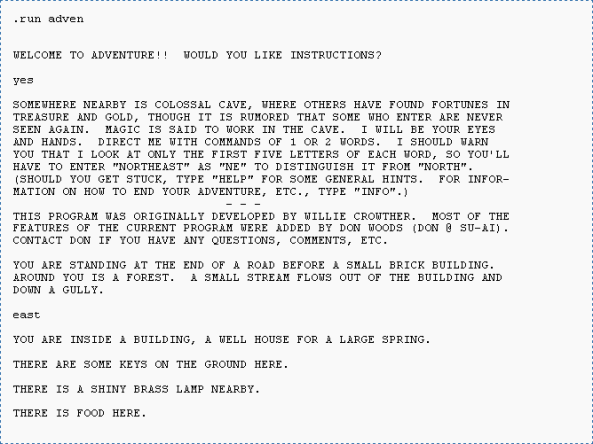

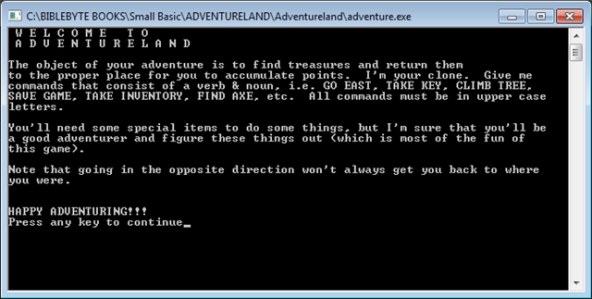

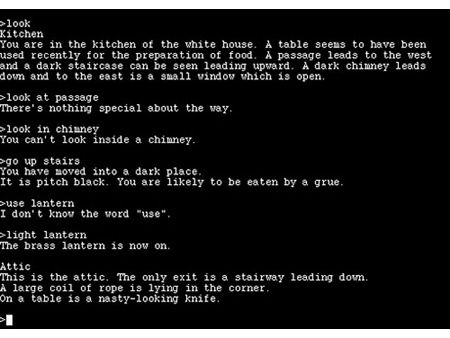

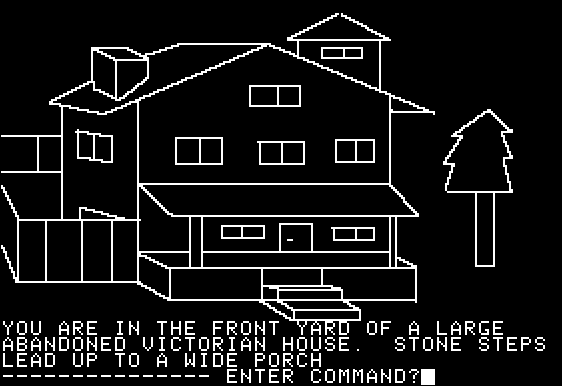

It’s hard to imagine something as different from Skyrim in its approach to story as the old adventure games were, though occasionally they could come close. I talked in the first installment of this post about how the early Infocom game Deadline created a surprisingly vivid, interactive world using only words and made me feel like I was actually living in that world, or at least visiting it, for the duration of the game’s 12-hour story. Honestly, though there were more technically impressive adventure games in later years, especially when graphics were added to the equation, I don’t think I ever played another adventure game that had the combination of story and personal freedom that Deadline did. That may well be because game players were put off by the sheer freedom that Deadline allowed. They didn’t know what do with it. They were used to games that pushed them down a single, linear path where the player’s next move was always obvious, leaving little room for nonlinear exploration. I remember people complaining about having to talk to suspects in Deadline because they had no idea what to ask. I’ve heard many of the same complaints about the Elder Scrolls games. People find themselves plunked down in the middle of a vast and complex world and have no idea what to do. Funny, I’ve never had any trouble figuring out what to do in these games. I do the same thing I’d do if I found myself plunked down in a strange city on a Saturday night. I walk around looking for fun and excitement.

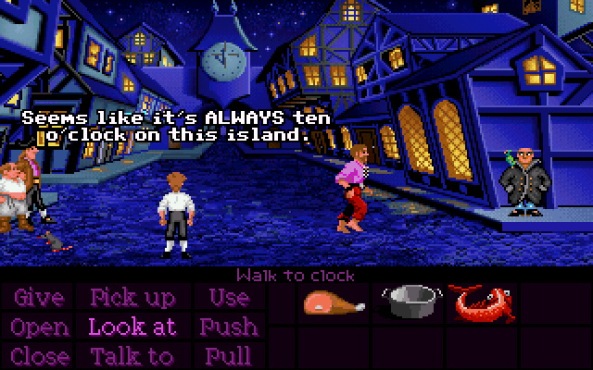

But after Deadline, most adventure games became fairly linear, at least by comparison with Deadline or Skyrim, and the player was usually given a clear-cut goal plus a series of problems that had to be solved in order to reach that goal. This could be fun if cleverly done (my favorite later adventure games were the ones from LucasArts, the Monkey Island games in particular), but after a while it got boring. By the late 1990s adventure games were largely dead, at least in the United States. European adventure games would occasionally reach these shores and threaten to revive the genre, but none really succeeded. A few persistent adventure game designers in the U.S., like Jane Jensen, continued to design games for indie publishers, but faced an uphill struggle to get those games to a wide audience.

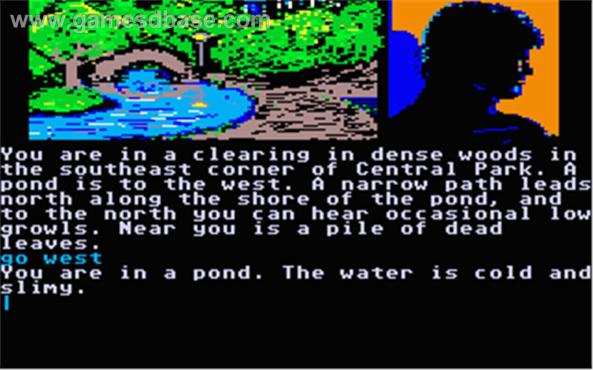

Then, around 2007, a company called Telltale Games, staffed in part by former employees of LucasArts, began to reignite interest in the genre. They began by taking some of the best of the old LucasArts franchises, like Monkey Island and Sam & Max, and producing new, shorter installment of them, treating them like episodes of a television show and publishing them in “seasons” consisting of five or six games apiece, often involving a continuing story line. The games were sharply produced, with excellent graphics and clever puzzles, drawing old adventure game fans like me back out of the woodwork and creating new fans largely through word of mouth. Pretty soon Telltale had become the new LucasArts and was developing games around franchises other than old adventure games, like the Back to the Future films and Jurassic Park.

Their most successful franchise to date, one that has garnered Telltale a raft of awards and apparently a substantial number of sales, is one based on the AMC-TV series The Walking Dead, probably the most popular original program currently running on basic cable. (Amy and I just finished watching the fourth season and are huge fans.) Games based on other media, especially movies, have a shaky reputation, because they tend to be, well, bad. There are any number of reasons why, including the need to produce them quickly so they’ll come out with the movie, the expense of acquiring the franchise rights (which siphons money out of the game-design budget), and the differences between movies and games. Movies and TV shows have fixed stories, while games are interactive and the player should be allowed to change the story. But how do you allow a player to change a story that the player already knows the end of, having seen it in the theater?

I don’t know what it cost Telltale to acquire the rights to The Walking Dead, but they’ve come up with a clever way of dealing with story. Instead of following the characters and plot points of the TV show, they’ve created an entirely new group of characters experiencing the same zombie apocalypse that the show’s characters are dealing with. This allows them to tell a completely different story, one where you don’t already know who will live and who will die, or where events will lead over the course of multiple “episodes.” As the player, you take the part of Lee Everett, a university professor who has been convicted of murdering his wife’s lover. For Lee, the apocalypse is both a tragedy and a blessing. As the game starts, Lee is being transported to prison by a police officer, whose squad car crashes when a “walker” — the main name the series uses for zombies — steps in front of it. In the resulting crash the officer dies and Lee escapes, only to encounter a young girl named Clementine whose parents have gone to Savannah, Georgia, and haven’t returned. The remainder of the story is about Lee’s attempt to reunite Clementine with her parents, an adventure during which the pair fall in with a group of apocalypse survivors each searching for their own salvation from the end of the world as they know it.

The cartoonishly “realistic” graphics of The Walking Dead Season One

The graphics in The Walking Dead, while more or less three-dimensional, are by no means photorealistic. In fact, they look faintly cartoonish, like rotoscoped images of real human actors given a comic twist. The story gives the illusion of interactivity and your choices in conversations and certain actions have an effect on the course of the game’s plot, but the effect is minimal. For instance, in an early scene from the game, if you lie to a farmer about how you wound up injuring yourself in the police car crash, he detects the lie and eventually expels you from his farm, forcing you to join others on a trip to Macon, Georgia. But if you tell him the truth, you still eventually end up on the trip to Macon, just for other reasons. No matter what you do, you’ll end up going to Macon, because that’s where the next section of the story takes place. (Hint: Never lie to anyone in The Walking Dead game. They always pick up on it and you inevitably do better, though only a little better, if you tell the truth.)

I’ve played through the entire first season of the game, albeit without that level of experimentation in most of it, but I suspect the level of interactivity remains about the same. Assuming you don’t do anything that gets you killed (which is quite easy to do in some scenes), you have some minor control over the details of the plot, but the broad story will continue on the same path no matter what you do. The designers of the game have done a brilliant job of making you feel as though you have freedom of choice in the game, but it’s only an illusion. You’re a puppet on a string, but the story is told well enough that it’s a string that’s fun to be on.

The Walking Dead: Season One is the antithesis of that virtual reality game I visualized back in 1981. The graphics are only semi-realistic, there’s very little freedom to branch out and explore, and the story is always going to come out the same. Yet they somehow make it fun and the story they tell is both exciting and moving — much like the TV show, if not quite as well written. I recommend it as a good story decently told, but if an open world is what you’re looking for, The Walking Dead: Season One is not the place to find it.

Dishonored

Dishonored was a surprise. I’d heard that it was a good game, but never imagined how deeply I’d get caught up in it or how its imaginary world would affect me emotionally. It’s a linear game, in the sense that it’s mission-based, much like the Call of Duty games, but in the Call of Duty games you feel like you’ve got a drill sergeant at your back the entire time, telling you where to run and where to shoot. In Dishonored you don’t have any choice as to what missions you go on, but once you’re on a mission your freedom is almost total and the number of options open for you in the environments where the missions take place and in the activities you can perform within those environments is surprisingly large. Dishonored is one of the most replayable games I’ve ever encountered, maybe not quite as much so as Skyrim but more so than any other basically linear, mission-based game I’ve yet seen. Arkane Studios, a subsidiary of Bethesda Softworks and its parent company ZeniMax Media, have absolutely outdone themselves with this game in terms of both storytelling and player freedom. I can’t recommend it wholeheartedly enough.

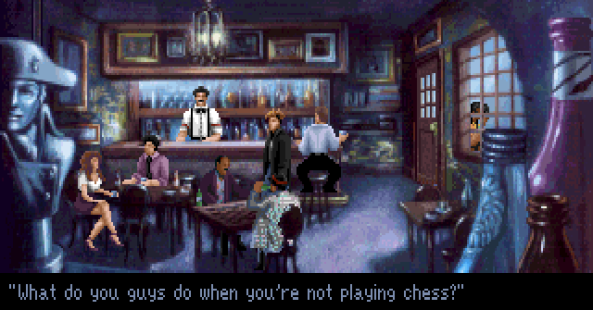

The stylized but not really cartoonish graphics of Dishonored

The setting is a steampunk version of some late 19th, early 20th century European/American society. You play the Empress’s personal bodyguard, who in the opening sequences is framed for her murder by the very people who have engineered it in an attempt at a palace coup. These blackguards have also kidnapped the Empress’s daughter, the rightful heir to the throne and (if rumor is to be believed) your own daughter as well. You are given a kangaroo trial, thrown in a maximum security prison and assigned an almost immediate execution date, but you escape with the help of a rebel underground that knows you’re innocent and wants you to rescue the young Empress so she can take the throne in place of the pretender who is overseeing the government.

That’s the set-up and each mission is engineered to bring you closer to this goal. Near the beginning you are given some cleverly conceived tools to help you in your missions by a godlike young man known only as the Other whom you encounter in a dream. You soon learn methods of acquiring more tools, the use of which is one of the most thrilling parts of the game. The most amazing tool is the heart, which is apparently the heart of a deceased young woman who doesn’t quite realize yet that she’s dead but who can whisper information to you about your surroundings when you hold her heart in your hand and activate it. This is a chillingly ingenious touch, not only useful but oddly moving. You also acquire a teleport device that allows you to jump from the street to ledges and from rooftop to rooftop, so you can move stealthily through the cities where the missions are set.

And stealth is crucial to this game. You can kill your enemies (or just the people who get in your way) using guns and bladed weapons, but the more you do so, the more chaotic the society becomes, and the more the plague that’s running through this society increases, because the dead bodies you leave behind attract rats, which spread the plague further. Simply put, the more dead bodies you leave in one mission, the more difficult the next mission becomes, until you find yourself fighting a lawless society and swarms of rats that can strip the flesh off your body in seconds if you don’t kill them first. You are much better off sneaking up on people and choking them into temporary unconsciousness than you are killing them, never mind that these “people” are just collections of pixels acting according to flowcharted scripts.

For me, the most stunning part of the game was the climax. I successfully achieved my goal, I thought, but I had played the game as though it were a shooter, killing whenever possible because it’s easier to play that way. But there are consequences to this kind of play and they caught me off guard when at the start of the final mission a character I’d considered a friend performed an act that startled the hell out of me. And what should have been a happy ending had a dark pall cast over it by the effects my action had on someone I loved. The final sequence is hallucinogenic in its intensity, as the Other takes you on an animated 3D tour of the acts you’ve performed throughout the game and you realize how insane some of your actions appear when viewed from outside time and space. Honestly, it took my breath away and I immediately started playing the game again, concentrating on killing as few people as I possibly could. There have been games in the past that have tried to enforce morality and consequences on the player, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it done as subtly and effectively as here.

Yes, Dishonored is linear in the sequence of its missions and offers nothing close to the vast, nonlinear landscape of actions and missions found in Skyrim, but the freedom allowed the player within the individual missions is so vast and the use of its tools so varied and imaginative that you feel like you lived through this story to a much greater degree than you feel like you lived through the story of The Walking Dead. Like that game, the graphics are stylized rather than hyperrealistic, as they are in Skyrim, but the games Goya-esque character models and the huge steampunk machines — the giant, whale-oil-fueled mecha suits that city guards wear in some of the towns are both amazing and terrifying the first time you see them storming rebels in the city streets — make the game such a unique experience that I’d be hard put to say whether I prefer this game or the more open Skyrim, which comes closer to my long ago dream of virtual reality. The Walking Dead, though its story pulls nicely on the player’s heartstrings, comes in a distant third as a piece of interactive storytelling because it’s ultimately so lacking in true interactivity.

Have we achieved the ultimate in virtual reality storytelling? Will we someday see my game about the Central American nation on the verge of revolution? In some ways, maybe we already have. In others…I suspect game designers still have some surprises up their sleeves in terms of realism and interactive storytelling but I can no longer guess what they might be.

I can’t wait until I see them, though. And hope I live to see a lot of them..