I was never a fan of the original Doctor Who. Maybe I would have been if I’d given it half a chance — a science-fiction-writer friend of mine was so enamored of it that he was guest of honor once at a Doctor Who convention — but whenever I’d catch a few minutes of it on my local PBS station it looked like a science fiction home movie filmed in someone’s basement. (I still can’t bring myself to sit through those old episodes, even though I’ve now got them on two different streaming services.)

But the new Doctor Who, rebooted in 2005 by Russell Davies, is different. For one thing, it looks like it was filmed in a much larger basement, one with a budget for special effects. Even that would be meaningless, though, without good actors, good characters and good writers. The new Doctor Who has those in spades and maybe the old Doctor Who did too; I’ll probably never sit still long enough to find out. Davies cast two wonderful Doctors, Christopher Eccleston (for only one season/series, alas) and David Tennant, and one of the best Companions ever, Britpop singer Billie Piper as Rose Tyler, with her dingbat mother Jackie (Camille Coduri), and deceptively useless boyfriend Mickey (Noel Clarke). Davies also gave stage actor John Barrowman probably the best television role of his career (Malcolm Merlyn on Arrow not excluded): the irresponsible, omnisexual Captain Jack Sparrow, who was later spun off to his level of incompetence on Chris Chibnall’s Torchwood, an unfortunate move. But that’s another story.

During Davies’ tenure a new writer, Steven Moffat (who had earlier created the Britcom Coupling), appeared on staff and wrote quite a few episodes, including a couple of brilliant ones, “Blink,” which introduced both the Weeping Angels and future movie star Carey Mulligan, and the two-parter “Silence in the Library/Forest of the Dead,” which introduced River Song (Alex Kingston), a time traveler who the Doctor didn’t know yet but who definitely knew him. There was no question that River Song would be back; she said as much. The real shock was the way, or several ways, in which she came back.

When Davies dropped out as showrunner after the David Tennant years, Moffat replaced him and recast the Doctor as Matt Smith, who played him with the same manic energy as his predecessors but also with a surprising edge of melancholy. Moffat also introduced a new companion, Amy Pond (Karen Gillan), who would go on to become as important to Smith as Rose Tyler had been to Eccleston and Tennant, perhaps more so, because her presence on the show ultimately revealed as much about the Doctor as it did about her. The first two-and-a-half seasons of Moffat’s tenure are basically the Amy Pond Cycle and despite the standalone nature of many of the filler episodes — you know, the ones that come between the two-parters — Moffat has managed to make everything seem more coherent, more of a whole, with recurring themes woven throughout a season or half season, even if only in the final moments of each episode: Amy repeatedly glimpsing a crack in space with light pouring out; Amy repeatedly glimpsing a woman with an eye patch staring at her through a rectangular hole; the Doctor repeatedly recalling his own death notice, the one he wasn’t supposed to see with the time and place of his demise printed on it. These recurring images gave each season a focus and the viewer a sense of what sort of startling developments they were hurtling toward.

Okay, if you’re much of a Doctor Who fan at all you probably saw all of this a while ago, but I’m running late and only catching up on the Moffat years now. If I’d known how good they were, I’d have done it sooner. But stick with me. I’m going somewhere here.

The Amy Pond Cycle — and I’ll explain why I call it a “cycle” in a moment, though if you saw it you can probably guess — explores a question that’s always hung over the series like a cloud, but to my knowledge has never been actually addressed on the show itself: Why does the Doctor need a Companion? Sure, the Companion is a kind of audience surrogate and a device for giving the doctor a sounding board for his thoughts and exposition, but you can’t rely for — What is it now? 36 years? — on a screenwriter’s crutch. The companions, who are almost always attractive young women, must mean something to the Doctor and it isn’t sexual (though Davies explored that angle by having Billie Piper’s Rose fall in love with David Tennant’s heartthrob Doctor).

But after some brief sexual tension in the beginning, it became clear that Amy Pond had no romantic designs on Smith’s Doctor. She loved her fiance Rory Williams (Arthur Darvill) and returned to marry him, with the surprising result that not only did Rory become a co-companion of the Doctor’s but an indispensable member of the cast. Whatever Amy meant to the Doctor, Rory came to mean it too. The idea that the Doctor is a child who likes to run off on impetuous adventures with his chums has been explored before, but never as intensely as Moffat explored it here. Smith’s ageless adolescence eventually outlasts the semi-ageless adolescence of the Ponds (who really should be the Williamses, or at least the Pond-Williamses, but only once, in what looked like it would be her final episode at the end of Season 6, does the Doctor finally call Amy by her married name).

Over time Amy manages to become mother to almost everybody on the show, including the Doctor, her husband and her daughter (and that last twist is so stunning that I’m not even going to mention it in case someone hasn’t seen it). And Rory, as the Centurion, actually manages to become older than the doctor, who’s only 1,200 years old, while Rory makes it to 2,000. Even Amy ages into perhaps her 50s at one point (though that timeline is erased.) In the end his chums have all outgrown him, or at least outmatured him, except perhaps for River, who drops in and out of his life like she drops in and out of the show (but is apparently seeing him on a nightly basis for a while after their marriage, as one episode implies). But it’s Rory, not Amy, who finally points out to the Doctor how irresponsible his flitting around randomly through space/time with innocent people on board the TARDIS is. In the end, the doctor actually outlives the Pond-Williamses (though the show conveniently ignores the fact that he could simply drop back into the 20th century and visit them any time he likes).

I call the Amy Pond era a cycle because — and you probably guessed this — it’s circular, ending with an explanation of why Amy was waiting for him in the first place, even as a little girl, and ends on a shot of her young face. The most significant things revealed about the Doctor during the Pond Cycle are that he can’t stand to be alone and he can barely stand to sit still. He can’t settle down to a normal family life, as he tries to do at one point with the Pond-Williamses. He has to be going somewhere constantly, almost as though he’s running from something, and what he’s running from seems to be loneliness, maybe the loneliness of being the last of the Time Lords, or maybe from his guilt at having been complicit in the destruction of his homeworld, Gallifrey. (Note: Gallifrey is apparently revealed in an upcoming episode to still exist in an alternate universe. How that will affect the Doctor I don’t know, but I suspect it will be up to Peter Capaldi’s Doctor to show us and from the couple of Capaldi episodes I’ve seen, he’ll be different in a number of ways.)

The companions, then, are a hedge against loneliness. But why are they almost always attractive young women? I haven’t watched many of the Clara Oswald episodes yet, but when he meets her (for the second time, as he finally realizes) in “The Snowmen” and asks her to sail away with him on the TARDIS, she asks, “Why me?” And he responds (I’m QFMing here), “I never know why. I only know who.”

Which is about the best description of romantic love I’ve ever heard.

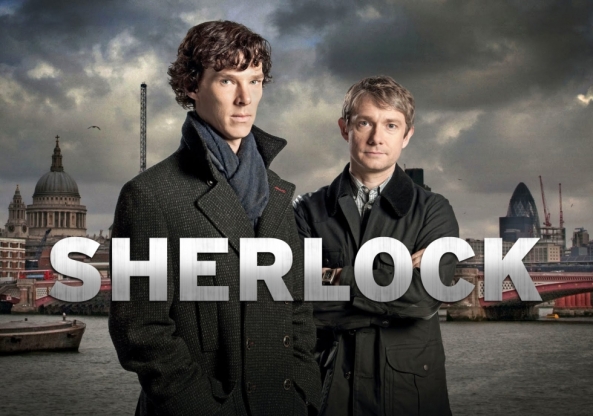

Sherlock

Meanwhile, Moffat has been running a second show based on an even more iconic character, Sherlock Holmes. He’s created (along with Mark Gatiss) what I regard as the best television version of Holmes to date and he’s done it by being faithful to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the only way that matters: in spirit. His Holmes has been lifted out of the late Victorian era and plopped down into our own as if by TARDIS, and the result is that the old stories, or new stories based on the old themes, seem fresh again, as Conan Doyle’s stories must have seemed back when the pages of The Strand hadn’t turned yellow and crumbly yet. It doesn’t hurt that Benedict Cumberbatch’s over-the-top yet tightly controlled performance catches Holmes’ arrogant self-confidence with such convincing bravado that you feel like you’re discovering the character for the first time, even if you finished reading the originals by the time you were out of middle school and read the Solar Pons stories afterward as literary methadone.

Moffat hasn’t given Sherlock the kind of overarching thematic structure that he magically imposed on Davies’ existing structure for Doctor Who. Instead it’s a show of moments, some large, some small, a great many of them brilliant. And getting better: My favorite moments are from the two most recent episodes, “The Sign of Three” and “His Last Vow,” specifically the drunken bachelor party (What could be better than being inside the head of a drunken Sherlock Holmes?), Holmes’ rambling toast at Watson’s wedding that went from insulting to moving (and I seem to recall that he solved a crime in there someplace too), and his slo-mo near-death sequence after being shot in the chest by an unlikely assassin (and if anything can be better than being in the head of a drunken Sherlock Holmes, it’s being in the head of a dying Sherlock Holmes trying desperately to deduce how NOT to be a dying Sherlock Holmes).

Sherlock could be accused of being everything from maudlin to too-clever-by-half, but that it can be these things and more in such an original and spectacular way is what makes it such transcendentally good TV. (No, I’m not sure what “transcendentally” means either, but I’m not using it to talk about meditation.) The visual innovations are particularly impressive. Some of them remind me of the screen tricks that the CSI shows have been pulling since the early 2000s, but when the first episode began with comical text messages appearing above the cell phones of a room full of reporters at a press conference, I knew that I’d stay with the show for its visual bravura alone and immediately called Amy in to watch with me. (The first season had just hit Netflix.)

It isn’t just the brilliance of Moffat and Gatiss that makes Sherlock so good. It’s seeing Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman in what will probably be the best roles they’ll ever be offered and, for Cumberbatch at least, the one that will lead off his obituary several decades from now. Cumberbatch’s talents are so unique that he’s a difficult actor to cast, but in the right role he’s the Olivier of our age. (I suppose that’s self-contradictory in that what made Olivier stand out was his extraordinary range; he was never typed by a single part, not even Heathcliff or his immortal Hamlet. Cumberbatch has range too, but he’s so much more interesting at this end of it that I don’t even enjoy watching him at the other.)

If Cumberbatch goes down as the great British actor of our era, I think Moffat will go down as the great British showrunner of our era — and maybe just the greatest showrunner period. I hope he turns down requests to go Hollywood, except perhaps to develop something for HBO, because there’s something quintessentially English in his style. But if he has the showrunner’s equivalent of Olivier’s range, maybe he can do something quintessentially American too. I’d just rather he not come up against the Hollywood executives who have made such an uneven hash out of the career of his American equivalent, Joss Whedon (and don’t even get me started on J.J. Abrams). I want Moffat to remain forever an original — and as brilliant as he is now.